At a community meeting last fall, we asked our members if they feared being pushed out of South Los Angeles.

All hands were raised.

This spurred a conversation on rising rents and growing homelessness in South LA as well as the new sports stadium in Inglewood, the Metro Los Angeles Crenshaw line, and the expansion of USC─developments, which while exciting, didn’t really seem like they would benefit the people in that room. These community members mentioned just a few of the changes happening in South LA. From anticipated projects like the impending construction of the 32-story Reef redevelopment to the quiet closures of long time family businesses around USC, the landscape of South LA is changing rapidly, begging the question, “Who is this all for?”

“Investment in South LA is not benefiting working class people,” stated Mary Warren, a retired SCOPE member, who after finding no vacancies in senior housing complexes, struggled to find affordable housing in the community she’s called home for decades. Mary’s challenge in finding affordable housing is reflected in the numbers. Many South LA neighborhoods have seen gross median rents increase while wages in South LA have stagnated; in 2013, the median household income was $31,905, compared to $34,473 in 2000¹². These factors have made it so that over 68% of South LA residents are rent burdened, based on 2013 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. An unemployment rate of 14.6% for the area, only adds to community members’ vulnerability to displacement, especially for black residents who experience a particularly high rate of unemployment due to discrimination in hiring and structural barriers to employment ³. Furthermore, residents are already feeling the pressure to leave–a survey of over 800 residents conducted by SCOPE last year found that 45% of surveyed residents believed they would have to move within the next five years.

I-105: Investment and Displacement

An aerial view of a portion of land cleared for I-105. Photo by Jeff Gates (In Our Paths)

Fears around displacement aren’t just warranted by the numbers, they’re justified by a history that has shown that when investment comes to Los Angeles, the first ones to go are poor people of color. One of the most striking examples of this is the creation of the I-105 freeway. In the 1960s, the state of California began planning the I-105 through South Central and other predominantly low income and black communities. In 1970, the state began acquiring properties in the freeway right of way. The state’s acquisition left behind boarded homes and empty lots, some of which remained vacant for decades and reduced property values for remaining homes, thus delivering social and economic death blows to entire neighborhoods.

By the time the freeway was completed in 1994, the LA Times reported that over 8,000 homes in the project area had been condemned 4. Furthermore, the freeway, originally heralded for its capacity to reduce regional pollution by alleviating street congestion is now home to one of the most freight congested interchanges in the country, with neighboring communities bearing the health impacts of localized pollution. The I-105 destroyed the social cohesion and economic power of these communities while creating health inequity, demonstrating how investment processes of the past systematically disregarded the interests of low income communities and communities of color, and often treated them as sacrifice zones.

Because of the seven year injunction to stop construction of I-105 neighborhoods were frozen in transition. Anticipating the end to the court action, in 1980 Caltrans decided not to re-rent houses as they became vacant. Instead, the houses were boarded up, abandoned Photo/caption by Jeff Gates (In Our Paths)

Neighborhood Oil Drilling and Health Inequity

The case of the freeways along with the continuing operations of neighborhood oil drills display how development can create inequity. In South LA, oil drills are often located closer to homes and are less likely to have important health safeguards than they are in wealthier neighborhoods 5. The drills don’t appear to create community wide benefits like greater access to employment; rather many residents who live near these sites suffer from respiratory issues, frequent nosebleeds, headaches, and exacerbated asthma 6. Lack of transparency from the companies and little accountability from the city and state has permitted these activities to go essentially unregulated in predominantly black and brown communities in South LA and Wilmington but has allowed protections like buffer zones and protective enclosures to be in place for whiter neighborhoods.

Elba in front of the drill site in her neighborhood in South LA

Elba, a resident of the Jefferson Park neighborhood, experienced regular nosebleeds for over four years and joined the fight to end oil drilling when she learned that her neighbors were also experiencing similar health symptoms. After participating in numerous actions where residents from South LA and Wilmington provided emotional testimonies and pleas to city officials and private decision makers, she had this to say, “They just don’t care about our health.”

Investment For Us By Us

Elba’s statement, backed by the history of investment in South LA, warrant the question, “Who has reaped the economic, environmental, and social benefits of investment?” The answers reflect who decision makers, whether public or private, really value. In the case of neighborhood oil drilling, it hasn’t been the low-income communities of color in South LA and Wilmington. And in multiple cases of freeway expansion and creation, it’s not the neighborhoods that are paved over or the communities that must bear the health impacts of living next to a freeway. It is definitely not the small family businesses priced out of long held spaces due to the increased presence of USC. And it’s not the growing numbers of homeless and housing unstable people in South LA who watch as minuscule amounts of multi-billion dollar developments are designated for affordable housing. When community members are not prioritized in planning and implementation of investment, the social and political power of communities is eroded, local businesses and jobs are lost, and health inequities are created.

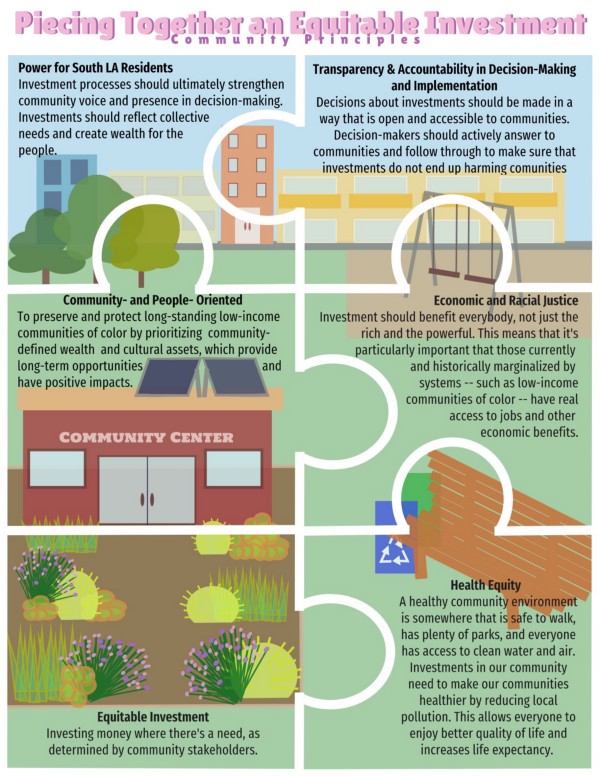

Community Investment Principles developed by South LA residents in 2017

How do we radically change a system of investment that has historically harmed low income communities of color so that they actually benefit the people who live in South LA right now? Our community members have the answer. Last year, South LA residents came together to discuss the economic changes needed in the community. From those conversations, it was clear that community members agreed on six major principles for investment. First, unlike past investments in Los Angeles, investment planning processes should engage community members in ways that are comprehensive and ongoing. Second, decision-making and implementation processes must be transparent to ensure that community members are informed of the changes happening in their neighborhoods and can hold decision-makers accountable to both promises and potential negative consequences.

In the case of neighborhood oil drilling, many residents weren’t aware when new wells were being drilled in their neighborhood, preventing them from taking actions to mitigate health impacts. Third, the investment itself should benefit longtime South LA residents, by addressing local needs and incorporating displacement avoidance measures. In contrast to freeway construction in the twentieth century, rail lines that are currently being built in low income communities of color should prioritize the needs of current residents, not a future demographic that may move in, and new transportation investments should work to ensure that the groups that rely on public transit the most can afford to stay and access new transportation options.

Our community members recognize that many of the problems and conditions in South LA are rooted in housing segregation, environmental racism, and systemic exclusion from economic opportunity. In order to begin remedying these historic and ongoing structural injustices, investment planning must use metrics that account for these disproportional outcomes and should prioritize economic, health, and racial justice. This means planning so that those who have traditionally been excluded from public investment because of their race, immigration status, or experience with the criminal justice system, can benefit.

Due to recently passed bond measures and cap and trade funds, there exists more potential than ever before to address long sought changes in our environment, housing, and transportation systems. At the same time, communities are feeling the threat of displacement more than ever before. We must shift a decades long framework of investment in Los Angeles that has bred inequity to one that prioritizes South LA, and ensure all Angelenos have the opportunity to thrive.

This is the second part of our South LA to Stay series, a blog and video project where we will be delving into the environmental and economic conditions South LA residents face everyday — from air pollution to fears of being pushed out by new development to lack of access to living wage jobs. Through this project, we hope to share stories of our residents’ resiliency by highlighting why they have chosen to stay in South LA after decades of disinvestment and the changes they demand in environment, jobs, housing, and economic development so that our communities can be in South LA to Stay.

¹ Urban Displacement. Accessed February 1, 2018 http://www.urbandisplacement.org/map/socal#.

² “2013 American Community Survey 5 Year Estimates.” U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed February 1, 2018. http://ftp2.census.gov/.

³ 2013 American Community Survey 5 Year Estimates.”

4 Guthrie, Mary. “A Century of Emotions: Photos Document Effects of 105 Freeway on Displaced Residents.” LA Times. March 16, 1995. Accessed February 1, 2018. http://articles.latimes.com/1995-03-16/news/hl-43379_1_century-freeway

5 “Oil Drilling in Los Angeles: A Story of Unequal Protections.” Community Health Councils. Los Angeles, 2015. Accessed February 1, 2018. https://climateaccess.org/system/files/CHC-Issue-Brief-Oil-Drilling-In-Los-Angeles.pdf

6 “Drilling Down.” Liberty Hill Foundation. Los Angeles, 2015. Accessed February 1, 2018 https://www.libertyhill.org/sites/libertyhillfoundation/files/Drilling%20Down%20Report_1.pdf