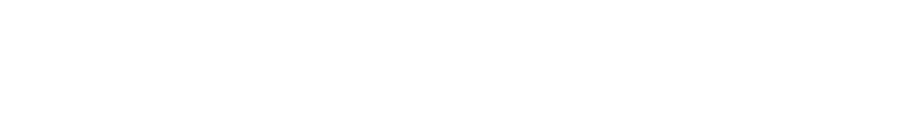

Fifty years ago, 1,300 black sanitation workers went on strike in Memphis, Tennessee after Echol Cole and Robert Walker were tragically crushed to death while on the job. Having reached a breaking point, the sanitation workers went on strike to demand a safe work environment, decent wages, better benefits, the right to form a union, and an end to racial discrimination in promotions─demands that affirmed their human dignity. Recognizing the Memphis sanitation workers’ struggle as part of the racial, economic and political injustice that oppressed black communities across the country, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. publicly supported the striking sanitation workers.

Fifty years ago, 1,300 black sanitation workers went on strike in Memphis, Tennessee after Echol Cole and Robert Walker were tragically crushed to death while on the job. Having reached a breaking point, the sanitation workers went on strike to demand a safe work environment, decent wages, better benefits, the right to form a union, and an end to racial discrimination in promotions─demands that affirmed their human dignity. Recognizing the Memphis sanitation workers’ struggle as part of the racial, economic and political injustice that oppressed black communities across the country, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. publicly supported the striking sanitation workers.

On this day, fifty years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated just after he held a rally for the sanitation workers and right as he was beginning the Poor People’s Campaign, which connected poor and working people across race to demand economic and human rights including basic income and public service jobs.

Fifty years later in South LA, the demands made by the Poor People’s Campaign remain relevant in our communities. Fifty years later in South LA, the discrimination and working conditions that Dr. King and the sanitation workers spoke out against, persist.Discrimination based on race, immigration status, and experience with the criminal justice system remain huge barriers to accessing jobs and upheavals in the manufacturing industry and the public sector have reduced the number of living wage jobs available to residents. The average South LA worker makes sixty cents on the dollar compared to the average LA County worker, whereas in 1960, South LA workers made eighty cents on the dollar, showing that in some measures, conditions have actually worsened.¹

The History of Work in South LA

A bird’s eye view of the massive South Gate Firestone plant in 1955 (Kelly Howard, LA Public Library Archives)

Understanding South LA’s economic conditions today requires understanding the nature of work in its past. During WWII labor shortages and the passage of anti discrimination laws opened up opportunities in the steel, aerospace, car, tire, and furniture manufacturing industries as well as the public sector for African Americans migrating to Los Angeles. For the first time, Black workers in South LA could access middle class union jobs at nearby plants like Firestone, Goodyear, and General Motors. At its peak, the manufacturing industry employed 24.2% of Black men and 18% of Black women in Los Angeles county.² The war also opened up opportunities for Black women in public sector clerical work and by 1960, almost 16% of employed Black women in Los Angeles worked in the clerical sector.³

This relatively short period of economic stability began to come to an end in the 1960s, when nationally, companies were leaving the central city for suburbs, other states with lower wages and less protective labor laws, or other countries entirely. Within the span of a year between 1963 and 1964, twenty eight industrial manufacturing plants left South Central and East Los Angeles.⁴ Between 1979 and 1982 alone, it was estimated that 70,000 jobs in South LA were lost.⁵ To put the massive scale of this economic shift into context━all of LA County lost 89,000 manufacturing jobs in the ten year period following the recession.⁶ The decline of the manufacturing industry coincided with the proliferation of low wage, non-union work in South LA as the garment and apparel industry rose and more and more South LA residents had to turn to service industry jobs in other parts of the city. Low wages, inadequate benefits, and often unsafe-these jobs mirror many of the conditions the sanitation workers protested fifty years ago.

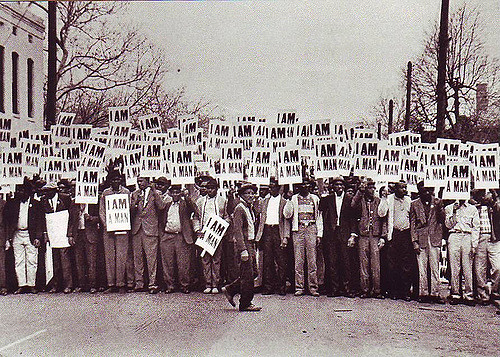

Workers at GM picking up their last checks (1982, Mike Sergieff, LA Public Library Archives)

The decline of job centers in South LA and the disinvestment that followed has resulted in Supervisorial District 2, which encompasses South LA, having the lowest jobs to person ratio in LA County.⁷ Not only are there physically fewer jobs located in South LA as a result of industry loss and the disinvestment that followed, but residents encounter a number of systemic barriers in accessing a sustainable livelihood.

Transportation

Access to affordable and reliable transportation remains one of the largest barriers to employment for South LA residents. The decline of the manufacturing industry in South LA and the growth of jobs elsewhere created a gap between job centers and South LA residents. In 1960, Black workers who were forced to look outside of South LA for jobs cited transportation as a major obstacle. Discriminatory lending practices limited car ownership opportunities for people of color in South LA and the streetcar system, which once connected South LA to other parts of the city, was dismantled in favor of freeways by the early 1960s.⁸ This barrier to accessing work has not changed.

“A lot of these jobs aren’t in South LA,” said Pat Jones, a SCOPE member who works multiple jobs and also serves as a minister at a local church. “They’re in other parts of the city or way out in other counties with lower minimum wages. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve heard young folks in my congregation say they can’t get to work because they don’t have enough money for gas or a train.”

Ninety three percent of employed South LA residents work outside of their council district and nearly a quarter depend on public transportation to get to work, which riders have often described as inconsistent and inefficient.⁹

Race and Immigration

A 2011 survey of South LA residents found that racial discrimination and immigration status presented the biggest challenges to finding stable quality work. While labor shortages and the passage of antidiscrimination laws opened up opportunities for Black and Latino workers in the 1940s and 1950s, the structure of the lower wage, non-union economies that followed allowed for racial discrimination and abuse of immigrant workers to go unchecked.

Pat experienced this first hand while looking for work as a homecare provider. “I got my certification but then when I started interviewing in other parts of the city, it felt like people didn’t want to hire me because they didn’t want a black woman working in their home.”

Pat’s experience is not uncommon; in fact, it’s well documented. Black workers, in particular, are subject to more discrimination in hiring and in the workplace, impacting employment rates and pay.¹⁰ Additionally black undocumented workers and immigrant workers in general are often blocked from higher wage jobs due to immigration and documentation status, pushing these groups into unsafe, low wage jobs with few protections.

Experience with the Criminal Justice System

Because of the state’s practice of over-policing and incarcerating black and brown people, experience with the criminal justice system is another major barrier to employment in South LA. The area has one of the largest formerly incarcerated populations in LA County. However, lack of supportive services and limited job training opportunities for reentry populations have shut doors for a large portion of our community.¹¹ Adding to this is the lingering impact of employment background checks which were lawful in LA until recently. Experience with the criminal justice system, transportation, race, and immigration status are just a few main barriers to work in South LA but in reality, residents may experience not one, but multiple challenges in obtaining a job, including lack of child care, pre-employment exams, and English proficiency, to name a few.¹²

An Economy That Works For All People

The fact that conditions have stagnated or even worsened over the past fifty years point to the need for a transformational shift in our local economy-from one that works people to one that works for people of different races, educational backgrounds, and who encounter multiple barriers to employment. As Dr. King was beginning to advocate for in his economic justice agenda, this transformational change should begin within the public sector. During the recession, 5000 jobs in the City of LA were cut, hitting communities like South LA, where the public sector was one of the largest employers and where neighborhoods depended on vital city services, the hardest.¹³ Four years ago, SCOPE, community organizations and labor unions came together and successfully demanded that the City commit to hiring these 5000 jobs and commit to hiring from the community. However, these jobs haven’t reached our community members and vital city services like street cleaning and tree trimming are still lacking in our neighborhoods, contributing to safety issues.¹⁴ It’s time the City honor its commitment to the people and restore these jobs, restore the vital services associated with these jobs and begin to restore the once thriving communities these jobs created. The City can do more by ending costly practices that contract work out instead of creating safe, living wage careers and also by committing to hiring those who face these barriers to work. It’s only through intentionally addressing the unique barriers South LA residents experience and understanding the harm created by past industries and policies can we create a South LA that is more economically just this year, next year, and fifty years from now.

This is the third part of our South LA to Stay series, a blog and video project where we delve into the environmental and economic conditions South LA residents face everyday — from air pollution to fears of being pushed out by new development to lack of access to living wage jobs. Through this project, we hope to share stories of our residents’ resiliency by highlighting why they have chosen to stay in South LA after decades of disinvestment and the changes they demand in environment, jobs, housing, and economic development so that our communities can be in South LA to Stay.

1.Ong, Paul, Andre Comandon, Alycia Cheng, Silvia Gonzalez. “South Los Angeles Since the Sixties.” University of California Los Angeles. 2018.

2. Sides, Josh. Post-Ghetto: Reimagining South Los Angeles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012. 35

3. Sides, Josh. L.A. city limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the present. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006. 91.

4. Ibid., 180.

5. Ibid., 180.

6. Masunaga, Samantha. “LA County has traded high paying jobs for low paying ones.” LA Times. Feb 22, 2017. http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-county-jobs-20170221-story.html

7. “LA County Supervisorial Districts.” Los Angeles Economic Development Corporation. April 2017.

8. Ong, Paul. 2018.

9. “Survey to Support Metro’s Equity Framework: Report on Findings.” EnviroMetro. March 13, 2018.

10. Amelia Wirts, Discriminatory Intent and Implicit Bias: Title VII Liability for Underwriting Discrimination, 58 B.C. L. Rev. 809, 811. 2017.

11. Davis, Lois. “Prisoner Reentry: As California release prisoners it must confront the public health consequences.”https://www.rand.org/pubs/periodicals/rand-review/issues/2011/winter/prisoner.html

12. Scott, M. E. Voices from Los Angeles: Barriers to Good Jobs and the Role of the Public Sector. Strategic Concepts in Organizing & Policy Education. 2011.

13. Pastor, Manuel. “Keeping It Real: Beyond Conflict and Coalition.” 2013 33–66.

14. “South LA Community Demands City Fix Broken Sidewalks.”

http://losangeles.cbslocal.com/2017/11/07/south-la-broken-sidewalks/